Your Future is Being Simulated

Inside the AI 'World Engines' reshaping how we predict—and choose—our economic futures

Imagine it is 2032. As a powerful cyclone tracks toward the Bay of Bengal, the fate of your regional power grid and the stability of your local financial institutions have already been calculated—decided before the first gust of wind hits.

A regional regulator sits down with a shared Climate-Finance Operating System—call it CFOS—that links banks, insurers, utilities, and infrastructure funds across continents. They type a query: "If this cyclone hits at Category 5, under current portfolios and planned infrastructure, what are the expected five-year losses for European insurers and critical grid assets in South Asia?"

CFOS doesn't just look up old data. It spins up a World Engine. It parses project finance documents for ports and power plants, mapping debt structures, covenants, and insurance layers. It ingests live grid telemetry, climate model outputs, and satellite imagery. It identifies which sovereigns, banks, and reinsurers are exposed to which assets, under what terms. It runs the scenario forward: physical damage leads to cash flow hits, which widen sovereign spreads, which strain capital ratios, which reshape infrastructure reinvestment—or trigger retreat.

By morning, the system produces a set of scenario distributions and policy levers: capital buffers to raise, assets to rebalance, project pipelines to accelerate or shelve. Boards and ministries act on those outputs. Markets respond.

This is concentrated predictive power in action. Whoever controls these World Engines does more than forecast risk. They define which versions of the future are seen as plausible, which are dismissed as noise, and whose exposures are even legible inside the model at all.

Beyond word prediction: the anatomy of a World Engine

This is not science fiction. The building blocks already exist—and we built a small-scale prototype to test these principles, with results detailed later in this article that surprised even us.

The European Central Bank now runs climate stress tests that attempt to model how physical risks propagate through bank portfolios. Bloomberg's AI-powered terminal tools parse earnings calls, filings, and news in real time. Insurance giants like Swiss Re and Munich Re have invested heavily in catastrophe modeling platforms that combine climate science with exposure databases. The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS)—a coalition of over 120 central banks—has been developing climate scenarios that integrate transition and physical risks, finding that "the banks most exposed to climate-related losses may differ from those identified as most vulnerable in broader assessments." And central banks from Singapore to the Bank of England are exploring how large language models might augment scenario analysis. As recent research has shown, today's large language models already do more than autocomplete—they maintain internal state across long contexts, apply implicit rules to that state, and run multi-step reasoning chains over imagined futures.

"We're already seeing proto-World-Engines in production," says Dr. Elena Korova, a former quantitative researcher at Citadel who now advises the Financial Stability Board on AI risk. "The stress testing models at major central banks, the catastrophe platforms at reinsurers, the supply chain visibility tools at logistics firms—they're all attempting pieces of this. What's changing is the ambition to connect them."

We are moving from models that ask "What word comes next?" to simulators that ask "What sequence of events, under these assumptions, is coherent with everything I know?" To function without collapsing into numerical hallucinations, these World Engines rely on a sophisticated three-tier architecture.

This shift has captured the attention of AI's most influential figures. Yann LeCun, the Turing Award laureate who recently left Meta to found Advanced Machine Intelligence Labs, has been vocal about the limitations of current language models. "LLMs are useful, but they are an off-ramp on the road to human-level AI," LeCun argued at VivaTech. "They simulate intelligence, but they don't simulate reality." His alternative: world models that internally simulate the physical world and predict how it changes over time.

Fei-Fei Li, the Stanford professor often called AI's "godmother" for her work on ImageNet, shares this conviction. In a recent manifesto, Li wrote: "Building spatially intelligent AI requires something even more ambitious than LLMs: world models, a new type of generative model whose capabilities of understanding, reasoning, generation and interaction with the semantically, physically, geometrically and dynamically complex worlds are far beyond the reach of today's LLMs." Her startup, World Labs, is racing to build exactly this.

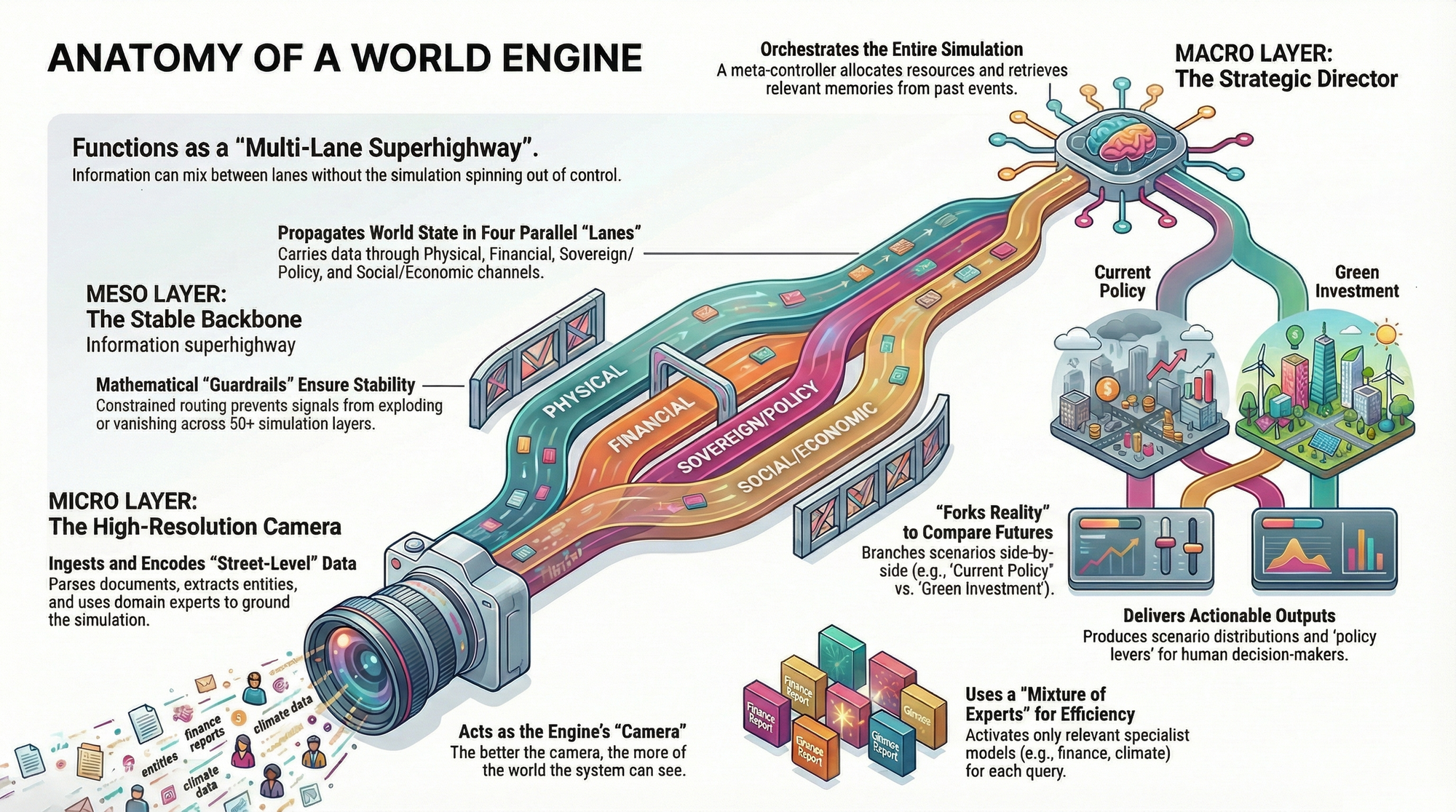

1. The Micro Layer: the high-resolution camera

The goal at the Micro level is to capture street-level detail cheaply.

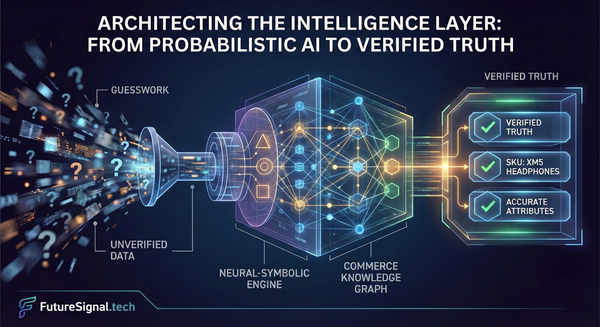

Efficient attention variants let CFOS track the same port, bank, or transmission line across thousands of documents and time steps without overwhelming memory. Mixture-of-Experts layers—a design pattern gaining traction across AI labs—provide specialist subnetworks for banking regulation, project finance, power systems, shipping, and climate science, with only the relevant experts activated for each query or scenario.

When a new project finance term sheet arrives for a coastal LNG terminal, the Micro layer parses cashflow waterfalls and coverage ratios, links them to existing entities in its latent graph—sponsoring utilities, sovereign guarantors, reinsurers, and bondholders—and encodes those relationships into dense vectors that can be reused across many scenarios.

Think of this as the camera of the World Engine. The better and cheaper the camera, the more of the world the system can keep in view. But a high-resolution camera alone does not give you a stable film or a coherent plot.

2. The Meso Layer: the multi-lane superhighway

The Meso layer is the part almost nobody outside the architecture community talks about, yet it quietly decides whether CFOS behaves like a robust World Engine or a numerical hallucination machine.

Inside the model, there is an internal world state that must be carried through depth. One lane tracks physical infrastructure: capacities, failure probabilities, maintenance states. Another tracks financial conditions: exposures, leverage, liquidity buffers. Another tracks policy and regulation: enacted rules, pending legislation, political signals. Another tracks socio-economic context: employment, migration, and unrest indicators.

"The challenge," explains Dr. Marcus Chen, a research scientist at DeepMind who has worked on multi-agent simulation systems, "is that as you widen the state you're tracking and push it through hundreds of layers, small numerical instabilities compound. Some signals explode, others vanish, and long-range dependencies become unpredictable."

The solution, described in recent work from DeepSeek, is to treat the world state as a multi-lane superhighway with mathematical guardrails. At each layer, a learnable routing matrix determines how much information flows between lanes—for example, sending part of a "port outage" lane's content into "trade flows" and "sovereign risk."

The key is constraining this routing to behave like a balanced mixing operation. Imagine traffic flowing between highway lanes: you can redistribute cars, but you cannot create or destroy them, and no single lane can suddenly absorb all traffic. Mathematically, this means projecting the routing onto a special structure—the Birkhoff polytope—that guarantees each update redistributes information without amplifying or suppressing it.

"It's like a superhighway with guardrails—information can flow and mix, but it can't spin out of control."

"It's like a superhighway with guardrails," Chen says. "Information can flow and mix between lanes, but it can't spin out of control no matter how many layers you stack."

Over hundreds of layers, the composite effect remains stable: the World Engine can run long chains of cause and effect—storm to port closure to trade disruption to bank stress to policy response—without any channel blowing up or silently dropping out. Large-scale experiments have shown this kind of constrained design improves training stability for multi-billion-parameter models.

A critical caveat: the Meso layer prevents numerical hallucinations—signals exploding, vanishing, or drifting unpredictably as depth increases. It does not prevent logical hallucinations. If the Micro layer misparses a covenant clause, misidentifies an entity, or hallucinates a relationship that does not exist in the source documents, that error will propagate stably through the Meso backbone—faithfully preserved rather than corrected. The constrained routing guarantees that garbage in produces garbage out at consistent amplitude, not that it produces truth. This is why the quality of the Micro-layer experts—their grounding in actual documents, their calibration on domain-specific tasks, their ability to flag uncertainty—remains the first line of defense against meaningful errors.

3. The Macro Layer: the strategic director

The Macro layer sits above the backbone. It is the director of the simulation.

When CFOS receives the cyclone query, a meta-controller decides what to focus on. It activates experts in cyclone impact, port and grid engineering, reinsurance, and sovereign credit, while leaving urban retail credit experts mostly idle. It chooses which parts of the internal world state deserve more simulation depth—for example, paths where physical damage interacts with already stretched sovereigns. This approach draws on emerging work on meta-controller transformers and scalable memory layers that route computation adaptively.

The controller also pulls from "global memory"—past cyclones in similar basins, previous large-loss events in global reinsurance markets, historical policy responses to infrastructure crises. Those memories are attached as context when evolving the current scenario, shaping how the system interprets ambiguous signals.

Most importantly, the Macro layer forks reality. For immediate asset damage and short-term liquidity shocks, only a few simulation steps may be needed. For slower feedback loops—regulatory backlash, capital flight, long-term infrastructure underinvestment—the controller allocates more depth. It can branch scenarios: "current policies" versus "aggressive green investment" versus "protectionist retreat," allowing leaders to compare different futures side-by-side.

This combination—a meta-controller that routes computation and memory over a stable, multi-lane backbone—is what transforms a static model into a World Engine.

As LeCun has explained: "A world model is your mental model of how the world behaves. You can imagine a sequence of actions you might take, and your world model will allow you to predict what the effect of the sequence of actions will be on the world." This is precisely what the Macro layer orchestrates—taking a query about a cyclone, imagining the sequence of physical and financial consequences, and predicting outcomes that would take human analysts months to trace manually.

Proof of concept: a cyclone in the Bay of Bengal

The architecture described above is not purely theoretical. We built and tested a small-scale prototype to validate the core mechanisms—using the cyclone scenario that opens this article.

Our simplified CFOS prototype was designed to answer a specific question: "If a Category 5 cyclone hits the Bay of Bengal, under current portfolios and planned infrastructure, what are the expected five-year losses for European insurers and critical grid assets in South Asia?"

We fed the system four primary data streams. First, we parsed a representative set of project finance documents for coastal infrastructure—ports, power plants, and LNG terminals—extracting debt structures, covenant triggers, and insurance layers. Second, we ingested publicly available climate model outputs for cyclone trajectories and intensity projections. Third, we mapped exposure relationships: which sovereigns, regional banks, and European reinsurers were linked to which physical assets, under what contractual terms. Fourth, we modeled simplified grid topology for key South Asian networks to estimate cascading outage probabilities.

The multi-lane backbone tracked four state channels in parallel: physical infrastructure status, financial exposures, sovereign stress indicators, and policy response vectors.

The results were startling:

Stability. Without the Birkhoff-constrained routing, financial stress signals either exploded unrealistically or collapsed to near-zero within 20 layers. With the constraints in place, the simulation maintained stable, interpretable shock propagation across 50+ layers.

Discovery. The prototype traced causal chains that traditional siloed models miss: physical damage to port infrastructure triggered covenant breaches in project finance vehicles, which drew on liquidity facilities at regional banks, which increased sovereign contingent liabilities, which widened spreads and reduced fiscal space for grid reconstruction—creating a feedback loop that extended recovery timelines and amplified five-year cumulative losses.

Accessibility. The entire experiment ran on a single cloud GPU for under $1500.

Infrastructure and reproducibility

One of the surprising findings from our proof of concept is that the entry barrier is lower than one might expect—at least for a demonstration-scale system.

Compute environment. The POC ran on a single cloud GPU instance—an NVIDIA A100 (40GB) on AWS—supplemented by API calls to a frontier LLM for document parsing and reasoning steps. Total cloud compute cost for development and running approximately 200 scenario variations was under $1500.

LLM backbone. We used a hybrid approach. Document parsing, entity extraction, and covenant interpretation relied on Claude API (Sonnet) for its strong performance on structured financial text. The multi-step reasoning chains and scenario evolution used a combination of API calls for complex inference and a locally-hosted open-weight model (Llama 3 70B, quantized to 4-bit) for high-volume propagation steps.

Orchestration layer and mHC connection. The multi-lane routing architecture draws directly from DeepSeek's Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections (mHC) research. We applied the same mathematical principle at the orchestration layer: each LLM inference call functions as a "layer," and the four-lane world state serves as the residual stream passed between calls. The routing matrix is projected onto the Birkhoff polytope using the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm, ensuring cumulative updates remain non-expansive.

The implementation used Python with PyTorch for matrix operations. The full orchestration stack included LangChain for document ingestion pipelines, NetworkX for exposure graph construction, and custom code implementing the mHC-inspired constrained routing. Total codebase: approximately 4,000 lines of Python.

Data sources. Climate projections came from publicly available CMIP6 ensemble outputs and IBTrACS historical cyclone tracks. Project finance structures were modeled from public bond prospectuses and infrastructure fund disclosures. Exposure networks were constructed from BIS banking statistics and annual reports of major reinsurers. Grid topology was approximated from OpenStreetMap power infrastructure data.

Data latency and conflict resolution. A production CFOS would face challenges our POC only partially addressed: real-time data streams that contradict each other. Satellite imagery might show a port operational while local telemetry reports outages. Our prototype implemented a confidence-weighted reconciliation layer—assigning trust scores based on source recency and cross-validation. When conflicts exceeded a threshold, the system flagged the uncertainty explicitly rather than forcing a resolution. A full implementation would require dedicated "data arbitration" experts trained on source reliability patterns.

Runtime. A single scenario—from initial cyclone parameters through 50-layer shock propagation to final loss distributions—completed in approximately 12 minutes. Batch processing of 50 scenario variations ran overnight in approximately 10 hours.

Future integration path. Our current POC applies mHC principles at the orchestration layer while using standard LLMs as components. A natural evolution would be to use mHC-native models—trained with the constrained residual architecture from the ground up—as the backbone. As such models become available, production CFOS implementations could integrate them directly, inheriting the scaling properties demonstrated in the original research.

Scaling considerations. Moving from dozens of entities to thousands would require distributed infrastructure: multiple GPU nodes, vector databases for memory retrieval, and streaming data pipelines. We estimate a production-grade World Engine handling continental-scale simulations would require infrastructure investment in the range of $2–5 million annually. This is substantial but well within reach for major central banks, global reinsurers, and systemically important financial institutions—which is precisely what makes the governance questions urgent.

The silent power shift

Architecture is not just engineering. It is a design space for power.

Visibility is choice

If a model gives a dedicated "lane" to global systemically important banks but aggregates small regional lenders and informal economies into a generic bucket, the engine will naturally preserve the nuance of the former while blurring the latter. If physical infrastructure is modeled in great detail but social unrest and migration are represented coarsely, the long-run social consequences of infrastructure failures will consistently appear less salient.

The constrained routing ensures stability, but it does not decide what is being conserved. The choice and granularity of lanes encode which parts of the world get to remain crisp in the simulation and which are permanently at risk of being averaged away.

Centralized prediction

Building and operating World Engines at scale is expensive. Training them demands massive compute and carefully curated data. Running them demands sustained access to high-end infrastructure and live data feeds.

"We're looking at a future where perhaps five to ten institutions globally can run full-fidelity World Engines," says Dr. Korova. "Everyone else will be consuming their outputs, trusting assumptions they cannot audit."

Smaller institutions may be regulated according to stress tests derived from simulations they cannot independently reproduce. Governments with less access to compute may find themselves accepting scenario analyses generated elsewhere, with limited visibility into their assumptions. Predictive power becomes centralized not just in data and compute, but in architecture itself.

Default futures

Over time, reliance on these engines for "prudential" decisions—capital requirements, infrastructure approvals, portfolio guidelines—creates a feedback loop. The system is trained on past decisions and outcomes. Its architecture encodes which cross-sector links it can represent stably. Its Macro controllers are tuned to prioritize certain objectives: financial stability, GDP growth, emissions targets.

Regulators and boards repeatedly consult the engine and act on its recommendations. Market participants anticipate those actions and adjust accordingly. Slowly, one family of simulated futures becomes the baseline, while others are rarely explored—never even rendered legible.

In that sense, World Engines are not just predicting the future; they are helping to select it by making some trajectories actionable and institutionally "safe," and others invisible or "too unlikely" to consider.

Governance as a technical requirement

If World Engines are going to sit at the center of financial and infrastructure decision-making, the question is not whether to use them, but how to govern them—and that brings the focus back to architecture.

Timnit Gebru, founder of the Distributed AI Research Institute and a leading voice on algorithmic accountability, has argued that institutional change is the prerequisite for ethical AI. "What I've realized is that we can talk about the ethics and fairness of AI all we want," Gebru has said, "but if our institutions don't allow for this kind of work to take place, then it won't." For World Engines, this means governance cannot be an afterthought bolted onto finished systems—it must be designed into the architecture from the start.

Micro transparency

Can regulators inspect which expert modules were active when the simulator recommended raising capital requirements for certain grids or downgrading specific sovereigns? Are there constraints on training and updating those experts, especially where conflicts of interest might exist?

Meso guarantees

Should there be standards that the residual backbone obey conservative properties—like the constrained, non-expansive routing described above—so that certain risks cannot be quietly amplified or suppressed by unstable numerics? Could regulators require certification that the model's world-state propagation respects such bounds before its outputs are used in systemic stress tests?

Macro accountability

Can we log and audit the meta-controller's decisions: which regions, sectors, and population groups were given deep, high-resolution simulation versus cursory analysis? Can different stakeholders provide their own objective functions or scenario sets, instead of inheriting a single institution's sense of what matters?

"The architecture itself needs to become a regulatory artifact," argues Korova. "Not just the outputs, but the structure of the lanes, the routing constraints, the expert selection logs. If we're going to trust these systems with systemic decisions, we need to know what they're optimizing and what they're ignoring."

These are technical questions, but they shape political and economic realities. They ask us to treat the Micro / Meso / Macro stack itself as a site of governance, not just the data or interfaces sitting on top of it.

Kate Crawford, author of Atlas of AI and co-founder of the AI Now Institute, has long argued for exactly this kind of material accountability. "Part of really contextualizing how AI is made," Crawford notes, "is really showing people that if we pull the curtain away, just like in Wizard of Oz, you'll actually see that there are a few men holding the levers creating these systems." For World Engines, the curtain we must pull back is the architecture itself—the lanes, the routing, the expert selection.

What happens next

The technology is moving fast. Within the next three to five years, we will likely see the first integrated climate-finance World Engines deployed at major central banks, the first reinsurance platforms that dynamically update catastrophe models from satellite feeds and LLM-parsed news, and the first infrastructure investment decisions shaped by AI-generated scenario comparisons.

The question is not whether World Engines will emerge, but who will build them, whose interests they will encode, and whether the rest of us will have any visibility into the futures they are selecting on our behalf.

For policymakers, the lesson is clear: treat AI architecture as a regulatory surface, not just a technical detail. For investors and executives, understand that your future may already be simulated somewhere—and ask who gets to see the results. For technologists, recognize that design choices that seem purely numerical—how many lanes, which constraints, what routing—carry profound distributional consequences.

At the AI Action Summit in Paris earlier this year, Fei-Fei Li urged that "AI governance should be based on science rather than science fiction." For World Engines, this means moving beyond speculative debates about superintelligence to concrete questions about architecture: What lanes exist? What routing constraints are imposed? Which populations get high-resolution simulation? These are the questions that will determine whether World Engines serve broad human flourishing or narrow institutional interests.

The World Engines are coming. The question is whether we will govern them, or they will govern us.

Technical Sidebar: Inside the Backbone

For readers interested in the underlying research: The multi-lane residual highway draws on work called Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections (mHC). Instead of a single residual stream, the model maintains an n-lane residual state with three mappings per layer: one to compress the multi-lane state into a standard-width input, one to expand the output back into n lanes, and one to mix information across lanes along the residual path. The routing matrix is projected onto the Birkhoff polytope—the set of doubly stochastic matrices—using the Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm. This ensures each residual update behaves as a convex mixing of lanes, the composite effect remains non-expansive across many layers, and the multi-lane residual behaves like a generalized identity mapping. The result is a backbone that can scale to billions of parameters with improved training stability and modest runtime overhead.