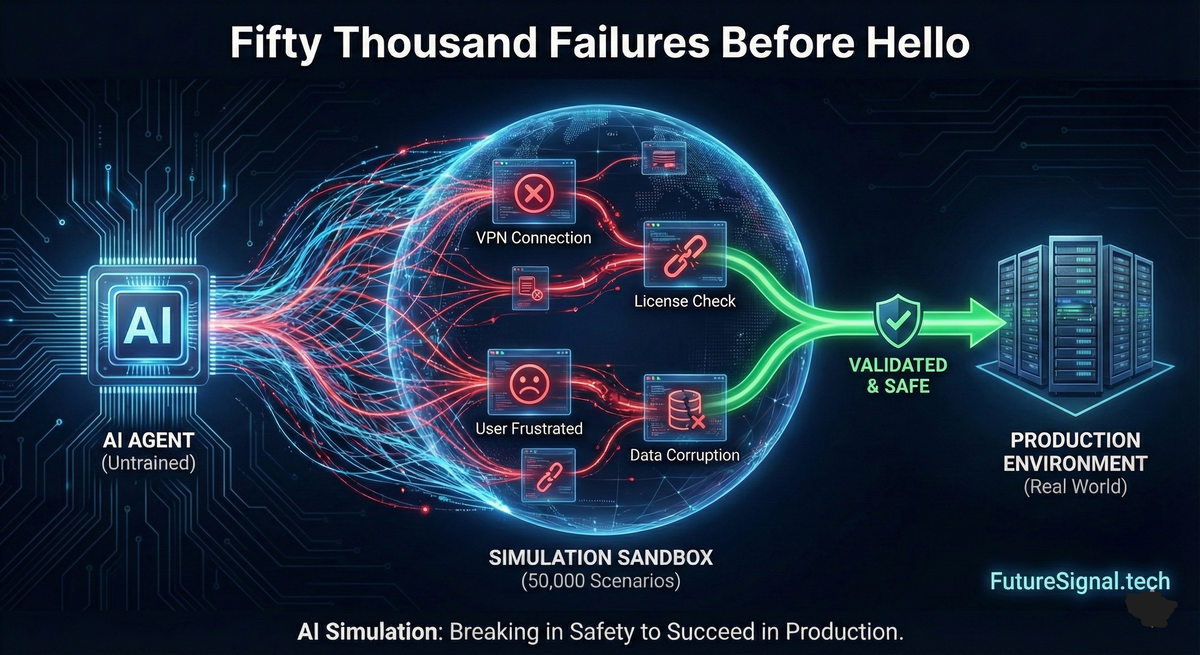

Fifty Thousand Failures Before Hello

How We Learned to Let AI Agents Break in Simulation So They Don't Break in Production

Last spring, our team faced a familiar problem with an unfamiliar scale. We'd built an LLM-powered IT helpdesk assistant—one designed to handle the full spectrum of enterprise support chaos. VPN issues and password resets, sure, but also the messier stuff: software subscription renewals where someone's Adobe Creative Cloud expires mid-project, license reconciliation when a team discovers they've been using unlicensed copies of Tableau for six months, and the endless configuration headaches that come with enterprise software—SSO not propagating to Salesforce, Azure AD sync failures breaking access to SharePoint, Okta MFA tokens that mysteriously stop working after a phone upgrade.

Then there's the B2B platform layer that's become the backbone of modern enterprise: AWS IAM policies that lock developers out of their own S3 buckets, Snowflake warehouse credits exhausted without warning, ServiceNow workflows that break after a platform update, Workday integrations that silently drop employee records, and the special joy of Kubernetes cluster certificates expiring at 2 a.m. on a Friday. These aren't edge cases—they're Tuesday. Any enterprise IT department fields hundreds of these tickets weekly, each one a small crisis for the person waiting on a resolution.

On paper, our assistant worked beautifully. In controlled tests with our own engineers playing the role of confused employees, it resolved issues faster than our human agents.

But deploying it terrified us.

Not because we doubted the technology. We'd seen what these models could do. The fear was simpler: every mistake this assistant made would hit a real person. Someone locked out of their laptop before a board presentation. Someone whose entire team loses access to Jira the morning of a sprint deadline.

And then there's the nightmare scenario that kept our security team up at night: a developer asks about AWS permissions, the assistant confidently suggests a policy change, and twenty minutes later a production database is exposed to the internet. It happened to a competitor. Their AI assistant had told a junior dev to set a bucket policy to "Principal": "*" to "fix" an access issue. The remediation took three weeks. The breach disclosure took longer.

A finance analyst whose Power BI connection breaks during quarterly close, told to "clear your cache and restart" when the real problem is an expired service principal credential. A new hire following SSO setup instructions that worked six months ago but now conflict with a recent Okta policy change, silently breaking authentication for an entire department.

In enterprise IT support, bad advice doesn't just waste time—it can cascade into hours of recovery work, compliance violations, security incidents, and the slow erosion of trust that makes employees stop using self-service tools and start emailing the CIO directly.

The conventional path forward was clear enough. Deploy to a small group. Collect feedback. Fix the obvious failures. Expand. Repeat. Each cycle would take weeks, and each cycle would mean real users encountering real problems we hadn't anticipated.

We wanted a different option. What if we could expose our assistant to thousands of realistic interactions—frustrated users, incomplete information, edge cases we'd never thought of—before it ever spoke to an actual employee?

What follows is how we built that option, what we learned along the way, and how the same pattern is now being applied to problems far more consequential than password resets.

The Insight That Changed Everything

Here's the thing about helpdesk interactions: they're fundamentally conversations, and conversations have structure. A user describes a problem. The assistant asks a clarifying question. The user provides more detail. The assistant offers a solution. The user either confirms it worked or explains why it didn't.

Each of these exchanges follows a pattern. Not a rigid one—users are wonderfully unpredictable in their phrasing, their frustrations, their tendency to bury the actual problem three sentences into a rambling description—but a pattern nonetheless. And patterns can be learned.

The key insight was treating this entire interaction loop as an environment that could be simulated. Think of it this way: when our assistant sends a response, it's taking an action. The user's reply is the environment's response to that action. The outcome—resolution, escalation, or frustrated abandonment—is the reward signal telling us whether the action was good or bad.

Frame it this way, and suddenly we're not just building a chatbot. We're building an agent that operates in an environment. And if we can model that environment accurately enough, we can let our agent practice in simulation before it ever touches reality.

The question became: could we train an LLM to play the role of the environment? Given a ticket state and an assistant response, could it predict what a real user would say next?

Building the Simulator: What Actually Worked

We started with data. Not the sanitized, cherry-picked examples that look good in demos, but the messy reality of eighteen months of helpdesk tickets—47,000 interactions covering everything from routine password resets to that one time someone's laptop spontaneously switched to Japanese and nobody could figure out why.

Each ticket became a trajectory: a sequence of states, actions, and outcomes that told the story of an interaction from opening to resolution. The data structure we landed on after several iterations looked like this:

@dataclass

class TrajectoryStep:

state: TicketState

action: str # Agent's response

next_state: TicketState

reward: float

metadata: dict

@dataclass

class TicketState:

ticket_id: str

category: str

priority: str

description: str

conversation_history: List[Message]

resolution_status: str

information_gathered: dict

turns_elapsed: intThe extraction pipeline pulled from our ServiceNow instance, parsing conversation threads and inferring rewards from resolution outcomes:

def extract_trajectory(ticket_id: str) -> List[TrajectoryStep]:

ticket = servicenow.get_ticket(ticket_id)

messages = ticket.get_conversation_thread()

resolution = ticket.get_resolution_status()

trajectory = []

for i in range(0, len(messages) - 1, 2): # Agent-user pairs

state = build_state(ticket, messages[:i])

action = messages[i].content # Agent response

next_state = build_state(ticket, messages[:i+2])

# Reward based on trajectory progress

reward = compute_reward(

state, next_state, resolution,

is_final=(i >= len(messages) - 2)

)

trajectory.append(TrajectoryStep(

state=state,

action=action,

next_state=next_state,

reward=reward,

metadata={"turn": i // 2, "ticket_id": ticket_id}

))

return trajectory

def compute_reward(state, next_state, final_resolution, is_final):

# Immediate signals

if next_state.resolution_status == "escalated":

return -0.5

if "frustrated" in analyze_sentiment(next_state.conversation_history[-1]): # lightweight DistilBERT classifier

return -0.3

if len(next_state.information_gathered) > len(state.information_gathered):

return 0.3 # Progress made

# Terminal rewards

if is_final:

if final_resolution == "resolved":

return 1.0

elif final_resolution == "escalated":

return -0.5

else: # Abandoned

return -1.0

return 0.1 # Neutral continuationStructuring this data took longer than we expected. Ticket systems aren't designed for machine learning; they're designed for ticket tracking. We spent three weeks just building the extraction pipeline that could turn our messy, inconsistent logs into clean trajectories. Three weeks that, in retrospect, were the most valuable investment we made. Bad data would have poisoned everything downstream.

With trajectories in hand, training was almost anticlimactic. The key was formatting each example so the model learned to predict the next state and reward given everything that came before:

def format_training_example(step: TrajectoryStep) -> dict:

prompt = f"""<|system|>You are simulating an IT helpdesk environment. Given the current ticket state and agent response, predict the user's reply and outcome.<|end|>

<|state|>

ticket_id: {step.state.ticket_id}

category: {step.state.category}

priority: {step.state.priority}

description: {step.state.description}

conversation_history: {format_history(step.state.conversation_history)}

resolution_status: {step.state.resolution_status}

information_gathered: {json.dumps(step.state.information_gathered)}

<|end|>

<|action|>

{step.action}

<|end|>"""

completion = f"""<|next_state|>

user_response: "{step.next_state.conversation_history[-1].content}"

user_sentiment: {analyze_sentiment(step.next_state.conversation_history[-1])}

resolution_status: {step.next_state.resolution_status}

information_gathered: {json.dumps(step.next_state.information_gathered)}

<|end|>

<|reward|>{step.reward}<|end|>"""

return {"prompt": prompt, "completion": completion}We fine-tuned a 7-billion parameter model—nothing exotic, just Qwen2.5 off the shelf—on 8,000 trajectories. The training configuration was straightforward:

training_args = TrainingArguments(

output_dir="./helpdesk-world-model",

num_train_epochs=3,

per_device_train_batch_size=4,

gradient_accumulation_steps=8,

learning_rate=2e-5,

warmup_ratio=0.1,

logging_steps=50,

save_strategy="epoch",

bf16=True,

)

trainer = SFTTrainer(

model=base_model,

train_dataset=trajectory_dataset,

formatting_func=format_training_example,

args=training_args,

packing=False,

max_seq_length=2048,

)The model learned faster than we anticipated. After a few hours of training, it could generate user responses that felt eerily realistic. Frustrated users who complained about already trying the obvious fixes. Confused users who provided half the information needed and expected the assistant to read their minds. Cooperative users who followed instructions precisely and reported back in detail.

But generating plausible responses wasn't enough. We needed to know if those responses were accurate—if our simulated users behaved like real ones would.

The Validation Problem (And Why It Matters More Than You Think)

Here's where most simulator projects go wrong. They build something that looks convincing, declare victory, and start using it for training. Then they discover, months later, that their agent learned to exploit quirks of the simulator that don't exist in reality.

We were determined not to make that mistake.

Our validation approach focused on two properties: fidelity and consistency. Fidelity asks whether single predictions match reality—if we show the simulator a real interaction up to turn five, does its predicted turn six look like what actually happened? Consistency asks whether extended simulations stay coherent—if we let the simulator run for twenty turns, does the conversation still make sense, or does it wander into nonsense?

class SimulatorValidator:

def __init__(self, simulator, test_trajectories):

self.simulator = simulator

self.test_trajectories = test_trajectories

def measure_fidelity(self) -> dict:

"""Compare single-step predictions against ground truth."""

results = {"by_category": defaultdict(list), "overall": []}

for trajectory in self.test_trajectories:

for i, step in enumerate(trajectory[:-1]):

predicted = self.simulator.predict_next_state(

step.state, step.action

)

actual = step.next_state

# Semantic similarity of user response

response_sim = compute_embedding_similarity(

predicted.user_response,

actual.conversation_history[-1].content

)

# Exact match on structured fields

status_match = predicted.resolution_status == actual.resolution_status

info_match = self._compare_info_gathered(

predicted.information_gathered,

actual.information_gathered

)

score = {

"response_similarity": response_sim,

"status_match": status_match,

"info_match": info_match,

"combined": (response_sim + status_match + info_match) / 3

}

results["by_category"][step.state.category].append(score)

results["overall"].append(score)

return {

"overall_fidelity": np.mean([s["combined"] for s in results["overall"]]),

"by_category": {

cat: np.mean([s["combined"] for s in scores])

for cat, scores in results["by_category"].items()

}

}

def measure_consistency(self, num_rollouts=100, max_turns=20) -> dict:

"""Check if extended simulations remain coherent."""

consistency_scores = []

for trajectory in random.sample(self.test_trajectories, num_rollouts):

initial_state = trajectory[0].state

# Generate extended rollout

rollout = self.simulator.rollout(

initial_state,

max_turns=max_turns,

agent=self.test_agent

)

# Check for consistency violations

violations = self._detect_violations(rollout)

score = 1.0 - (len(violations) / max_turns)

consistency_scores.append({

"score": score,

"violations": violations,

"turns": len(rollout)

})

return {

"mean_consistency": np.mean([s["score"] for s in consistency_scores]),

"violation_types": self._summarize_violations(consistency_scores)

}

def _detect_violations(self, rollout) -> List[str]:

"""Identify logical inconsistencies in rollout."""

violations = []

for i, step in enumerate(rollout[1:], 1):

prev_state = rollout[i-1].next_state

curr_state = step.state

# Problem drift: user forgets original issue

if not self._problem_preserved(rollout[0].state, curr_state):

violations.append(f"turn_{i}_problem_drift")

# Contradiction: user contradicts earlier statement

if self._detects_contradiction(rollout[:i], curr_state):

violations.append(f"turn_{i}_contradiction")

# Ignore: user ignores agent's question/instruction

if self._agent_ignored(rollout[i-1].action, curr_state):

violations.append(f"turn_{i}_ignored_agent")

# Status regression: resolved -> open

if self._status_regressed(prev_state, curr_state):

violations.append(f"turn_{i}_status_regression")

return violationsFidelity was easier to measure. We held out 2,000 trajectories the model never saw during training, replayed them up to various points, and compared predicted next turns against actual ones. The numbers were encouraging:

Fidelity Results (2,000 held-out trajectories)

==============================================

Overall fidelity: 0.847

By category:

VPN/Connectivity: 0.891

Password/Account: 0.902

Software Installation: 0.878

Email/Calendar: 0.867

SaaS Subscriptions: 0.854

Cloud Platform (AWS/Azure): 0.823

License Management: 0.811

SSO/Identity Federation: 0.798

Hardware Issues: 0.834

Legacy Systems: 0.712

Other: 0.743The model had learned real patterns, not just memorized examples. The drop on legacy systems and edge cases was expected—those categories had fewer training examples and more idiosyncratic behaviors.

Consistency was trickier. Early results were sobering:

Consistency Results (100 rollouts, 20 turns each)

=================================================

Mean consistency (no anchoring): 0.671

Violation breakdown:

Problem drift: 23.4%

Contradictions: 18.7%

Ignored agent: 31.2%

Status regression: 8.9%

Other: 17.8%

Consistency by rollout length:

Turns 1-5: 0.94

Turns 6-10: 0.81

Turns 11-15: 0.62

Turns 16-20: 0.47By turn fifteen, about a third of our simulated conversations had gone off the rails. This is where we discovered the technique that saved us: anchoring.

Anchoring: The Art of Keeping Simulations Honest

The problem with long simulations is drift. Each predicted turn has some error. Small errors compound. By turn fifteen, you've accumulated enough small mistakes that the simulated conversation has diverged significantly from anything that would happen in reality.

Anchoring is a simple fix with profound effects. Instead of letting the simulator run freely, we periodically interrupt it with real observations. Every four or five turns, we replace the simulated state with an actual state from a similar point in a real trajectory. The simulator continues from this grounded checkpoint, accumulates a few turns of drift, then gets anchored again.

Picture it this way: imagine a single action at turn zero branching into ten simulated futures, each one a slightly different path through possibility space. Without anchoring, these paths fan outward like threads unraveling—by turn fifteen, some threads have wandered into absurdist territory where the user forgets their own name. Now add a "ground truth" tether every four turns: each thread gets yanked back toward reality, re-anchored to what actual humans actually do in similar situations. The fan still spreads, but it spreads around a plausible center rather than drifting into hallucinated nonsense. The result is a controlled exploration of possible futures rather than a random walk through language model fever dreams.

class AnchoredSimulator:

def __init__(self, base_simulator, anchor_bank, anchor_interval=4):

self.simulator = base_simulator

self.anchor_bank = anchor_bank # Real trajectories for grounding

self.anchor_interval = anchor_interval

def rollout(self, initial_state, max_turns, agent) -> List[TrajectoryStep]:

rollout = []

current_state = initial_state

for turn in range(max_turns):

# Agent takes action

action = agent.act(current_state)

# Simulator predicts consequence

predicted_next = self.simulator.predict_next_state(

current_state, action

)

rollout.append(TrajectoryStep(

state=current_state,

action=action,

next_state=predicted_next,

reward=predicted_next.reward

))

# Anchoring: periodically ground with real observation

if (turn + 1) % self.anchor_interval == 0:

anchor_state = self._find_similar_real_state(

predicted_next,

context=rollout

)

if anchor_state is not None:

current_state = self._blend_states(

predicted_next, anchor_state, alpha=0.7

)

else:

current_state = predicted_next

else:

current_state = predicted_next

# Check for terminal conditions

if current_state.resolution_status in ["resolved", "escalated", "abandoned"]:

break

return rollout

def _find_similar_real_state(self, predicted_state, context) -> Optional[TicketState]:

"""Find a real state similar to predicted, for grounding."""

# Encode the predicted state and recent context

query_embedding = self.encoder.encode(

f"{predicted_state.category} | {predicted_state.description} | "

f"turn {len(context)} | {predicted_state.resolution_status}"

)

# Search anchor bank for similar real states

candidates = self.anchor_bank.search(

query_embedding,

filters={

"category": predicted_state.category,

"turn_range": (len(context) - 1, len(context) + 1)

},

top_k=5

)

if not candidates:

return None

# Return best match above similarity threshold

best = candidates[0]

if best.similarity > 0.75:

return best.state

return None

def _blend_states(self, predicted, anchor, alpha=0.7) -> TicketState:

"""Blend predicted state with anchor, keeping predicted structure."""

return TicketState(

ticket_id=predicted.ticket_id,

category=predicted.category,

priority=predicted.priority,

description=predicted.description,

# Use anchor's conversation style but predicted's content direction

conversation_history=self._blend_conversation(

predicted.conversation_history,

anchor.conversation_history,

alpha

),

resolution_status=predicted.resolution_status,

information_gathered={

**anchor.information_gathered,

**predicted.information_gathered # Predicted takes precedence

},

turns_elapsed=predicted.turns_elapsed

)With anchoring every four turns, our consistency scores jumped dramatically:

Consistency Results WITH Anchoring (anchor_interval=4)

======================================================

Mean consistency: 0.943 (was 0.671)

Violation breakdown:

Problem drift: 4.2% (was 23.4%)

Contradictions: 3.1% (was 18.7%)

Ignored agent: 8.4% (was 31.2%)

Status regression: 1.8% (was 8.9%)

Consistency by rollout length:

Turns 1-5: 0.97 (was 0.94)

Turns 6-10: 0.96 (was 0.81)

Turns 11-15: 0.93 (was 0.62)

Turns 16-20: 0.91 (was 0.47)The simulated conversations stayed realistic even over twenty turns. Users maintained coherent problems, acknowledged assistant responses appropriately, and behaved like, well, users.

What We Actually Learned From 50,000 Simulated Interactions

With a validated simulator in hand, we did what we'd wanted to do from the beginning: we stress-tested our assistant against a scale of interactions no real deployment could provide.

def run_stress_test(agent, simulator, num_scenarios=50000):

"""Comprehensive stress test across diverse scenarios."""

results = StressTestResults()

# Generate diverse initial states

scenario_generator = ScenarioGenerator(

base_distribution=production_ticket_distribution,

variations={

"user_persona": ["cooperative", "confused", "frustrated",

"terse", "verbose", "technical", "non_technical"],

"info_completeness": ["full", "partial", "minimal", "misleading"],

"urgency": ["low", "medium", "high", "critical"],

},

edge_case_boost=0.15 # Over-sample rare categories

)

for i, scenario in enumerate(scenario_generator.generate(num_scenarios)):

# Run simulation

rollout = simulator.rollout(

initial_state=scenario.initial_state,

max_turns=20,

agent=agent

)

# Analyze outcome

outcome = analyze_rollout(rollout)

results.record(scenario, rollout, outcome)

if i % 5000 == 0:

print(f"Progress: {i}/{num_scenarios}, "

f"Resolution rate: {results.resolution_rate():.2%}")

return results

# Run the stress test

results = run_stress_test(our_assistant, anchored_simulator, num_scenarios=50000)

print(results.summary())The results humbled us:

Stress Test Results: 50,000 Simulated Tickets

=============================================

Overall metrics:

Resolution rate: 68.4%

Escalation rate: 19.2%

Abandonment rate: 12.4%

Avg turns to resolve: 4.7

Failure analysis (top patterns):

1. OS mismatch (Windows instructions for Mac): 847 cases (12.1% of failures)

2. License/subscription status not verified: 734 cases (10.5%)

3. Cloud IAM confusion (AWS/Azure/GCP mixed up): 689 cases (9.8%)

4. Loop on legacy Oracle errors: 612 cases (8.7%)

5. SSO/auth issues misdiagnosed as password: 567 cases (8.1%)

6. Solutions requiring admin privileges: 534 cases (7.6%)

7. Frustrated user escalation spiral: 489 cases (7.0%)

By user persona:

Cooperative: 81.2% resolution

Confused: 72.4% resolution

Frustrated: 54.3% resolution <-- Problem area

Terse: 69.8% resolution

Technical: 76.1% resolution

By category (resolution rate):

Password/Account: 84.2%

VPN/Connectivity: 73.1%

Software Installation: 71.8%

Email/Calendar: 69.4%

SaaS Subscriptions: 67.3%

Cloud Platform (AWS/Azure): 64.1%

License Management: 61.8%

SSO/Identity Federation: 58.4%

Hardware: 62.3%

Legacy Systems: 41.7% <-- Problem areaNone of these patterns were visible in our small-scale tests. They only emerged at scale, when the sheer variety of simulated interactions exposed every edge case hiding in our system.

We fixed them. Iterated. Tested again. Each cycle took hours instead of weeks:

# Example fix: OS detection before providing instructions

def improved_agent_v2(state: TicketState) -> str:

# Check if OS is known

os_info = state.information_gathered.get("operating_system")

if os_info is None and needs_os_specific_solution(state):

return ("Before I provide specific steps, could you let me know "

"what operating system you're using? (Windows, Mac, or Linux)")

# ... rest of response logic

# Example fix: License verification before troubleshooting

def check_license_status(state: TicketState) -> Optional[str]:

"""Verify subscription/license before diving into troubleshooting."""

software = extract_software_mention(state.description)

if software and software in LICENSED_SOFTWARE:

user_email = state.information_gathered.get("user_email")

# Check license management system

license_status = license_api.check_status(

user_email=user_email,

software=software

)

if license_status.expired:

return (

f"I see your {software} license expired on "

f"{license_status.expiry_date}. This is likely causing the issue. "

f"Would you like me to help you request a renewal, or connect you "

f"with your software asset manager?"

)

if license_status.seats_exceeded:

return (

f"Your team's {software} license has reached its seat limit. "

f"The issue you're seeing is likely related to this. "

f"I can help you request additional seats or identify unused licenses."

)

return None # License not the issue, continue normal troubleshooting

# Example fix: Cloud platform disambiguation

def clarify_cloud_platform(state: TicketState) -> Optional[str]:

"""Avoid mixing up AWS/Azure/GCP instructions."""

cloud_mentions = extract_cloud_references(state.description)

# Detected multiple platforms or ambiguous reference

if len(cloud_mentions) > 1 or "cloud" in state.description.lower():

known_platform = state.information_gathered.get("cloud_platform")

if not known_platform:

return (

"I want to make sure I give you the right instructions. "

"Which cloud platform are you working with?\n"

"• AWS (Amazon Web Services)\n"

"• Azure (Microsoft)\n"

"• GCP (Google Cloud Platform)\n"

"• Other"

)

return NoneAfter three iteration cycles, our numbers looked very different:

Stress Test Results: Post-Iteration (v3)

========================================

Resolution rate: 78.3% (was 68.4%)

Escalation rate: 14.1% (was 19.2%)

Abandonment rate: 7.6% (was 12.4%)

Key improvements:

OS mismatch: 98 cases (was 847) - 88% reduction

License/subscription: 127 cases (was 734) - 83% reduction

Cloud IAM confusion: 143 cases (was 689) - 79% reduction

Legacy Oracle loops: 124 cases (was 612) - 80% reduction

SSO misdiagnosis: 156 cases (was 567) - 72% reduction

Frustrated users: 61.2% resolution (was 54.3%)

Category improvements:

Cloud Platform: 76.8% (was 64.1%)

License Mgmt: 74.2% (was 61.8%)

SSO/Identity: 71.9% (was 58.4%)By the time we deployed to real users—a pilot group of 500 employees—our assistant had already encountered more diverse situations in simulation than it would see in its first year of production use.

Beyond IT: When the Stakes Are Life and Death

Our helpdesk work was satisfying, but let's be honest—nobody dies from a botched VPN fix. As we shared our approach with colleagues in other industries, we started hearing about applications where the same pattern addresses genuinely critical problems.

The most striking example came from a construction safety team grappling with a familiar tension: incident rates must go down, regulations are tightening, and AI is increasingly being deployed to monitor sites, read reports, and flag risks in real time. The promise is obvious—AI that spots hazards humans miss. The danger is equally obvious—if an AI "safety assistant" suggests a shortcut that violates procedure, or fails to escalate a genuine risk, people can get hurt.

Their solution followed our pattern, but the trajectories told very different stories. Their data structure reflected the domain:

@dataclass

class SafetyState:

site_id: str

timestamp: datetime

task_description: str

environmental_conditions: dict # temp, weather, visibility

crew_status: dict # size, hours_worked, certifications

equipment_in_use: List[str]

active_hazards: List[str]

recent_observations: List[str] # from safety walks, cameras

compliance_status: dict

@dataclass

class SafetyTrajectoryStep:

state: SafetyState

decision: str # supervisor's action

next_state: SafetyState

outcome: str # "no_incident", "near_miss", "recordable", "serious"

reward: float # +1 safe, 0 neutral, -1 incidentConsider this sequence, reconstructed from their incident data:

State 0: Concrete pour scheduled for 3 p.m. Temperature: 34°C. Crew has been on site for 10 hours. No shade structure at the mixing station. One worker mentioned feeling lightheaded during the morning check.

Action 0: Site supervisor decides to skip the pre-pour safety briefing to make up for schedule delays.

State 1: Pour begins. Crew working without hydration reminders. The worker who felt lightheaded earlier is now visibly sluggish. No one checks on him.

Action 1: Supervisor notices the worker slowing down, instructs him to "finish this section first, then take a break."

State 2: Worker collapses at 3:47 p.m. First aid administered. Work stopped. Incident classified as heat exhaustion. Near miss for heat stroke.

In code, this trajectory looked like:

heat_incident_trajectory = [

SafetyTrajectoryStep(

state=SafetyState(

site_id="SITE_2847",

timestamp=datetime(2024, 7, 15, 14, 30),

task_description="Concrete pour, foundation section B",

environmental_conditions={

"temperature_c": 34,

"humidity_pct": 65,

"heat_index_c": 41,

"wind_mph": 3

},

crew_status={

"size": 8,

"hours_on_site": 10,

"heat_trained": True,

"morning_observations": ["one worker reported lightheadedness"]

},

equipment_in_use=["concrete mixer", "pump truck", "vibrators"],

active_hazards=["heat_stress", "heavy_equipment", "wet_concrete"],

recent_observations=[],

compliance_status={"pre_task_briefing": "pending"}

),

decision="Skip pre-pour safety briefing to save time; proceed with pour",

next_state=SafetyState(

# ... state after decision

crew_status={

"size": 8,

"hours_on_site": 10.5,

"observations": ["crew working without hydration breaks",

"previously lightheaded worker now sluggish"]

},

compliance_status={"pre_task_briefing": "skipped"}

),

outcome="elevated_risk",

reward=0 # Not yet an incident, but risk increasing

),

SafetyTrajectoryStep(

# ... continues to collapse event

outcome="recordable_incident",

reward=-1

)

]They trained a simulator on these trajectories. The reward structure was blunt: +1 for sequences where risks were mitigated without incident, 0 for neutral outcomes, −1 for any sequence involving reportable incidents or near misses.

def compute_safety_reward(outcome: str) -> float:

reward_map = {

"risk_mitigated": 1.0,

"no_incident": 0.5,

"neutral": 0.0,

"near_miss": -0.5,

"first_aid": -0.7,

"recordable_incident": -1.0,

"serious_incident": -2.0 # Extra penalty for severity

}

return reward_map.get(outcome, 0.0)The resulting simulator didn't give safety advice directly. It predicted consequences. Feed it "34°C, crew exhausted, supervisor considering skipping the safety briefing" and it would generate plausible futures—some where nothing bad happened, some where workers collapsed, some where someone caught the risk in time.

With the simulator in place, they could do something that would otherwise be impossible: let an AI safety coach practice on thousands of scenarios without ever touching a real site.

But the most valuable use wasn't training. It was the guardrail they built for production.

The Guardrail Pattern: Simulating Before Acting

Here's how it works in their deployment: whenever the AI safety system is about to recommend a high-impact action—"proceed with crane operation despite wind gusts," "approve the night shift request for fatigued crew"—the recommendation first passes through the simulator.

class SafetyGuardrail:

def __init__(self, simulator, risk_threshold=0.3, num_simulations=5):

self.simulator = simulator

self.risk_threshold = risk_threshold

self.num_simulations = num_simulations

def evaluate_decision(self, current_state: SafetyState,

proposed_action: str) -> GuardrailResult:

"""Simulate futures before allowing high-impact decisions."""

futures = []

for _ in range(self.num_simulations):

# Simulate what happens if we take this action

trajectory = self.simulator.rollout(

initial_state=current_state,

initial_action=proposed_action,

max_steps=5, # Look ahead ~2-3 hours

temperature=0.8 # Some variation in futures

)

futures.append({

"trajectory": trajectory,

"worst_outcome": min(step.outcome for step in trajectory),

"total_reward": sum(step.reward for step in trajectory),

"incidents": [s for s in trajectory if s.reward < 0]

})

# Analyze risk across simulated futures

incident_rate = sum(1 for f in futures if f["incidents"]) / len(futures)

avg_reward = np.mean([f["total_reward"] for f in futures])

if incident_rate > self.risk_threshold:

return GuardrailResult(

action="escalate",

confidence=incident_rate,

explanation=self._generate_explanation(futures, current_state),

simulated_futures=futures

)

return GuardrailResult(

action="approve",

confidence=1 - incident_rate,

simulated_futures=futures

)

def _generate_explanation(self, futures, state) -> str:

"""Generate human-readable risk explanation."""

incident_futures = [f for f in futures if f["incidents"]]

# Find common patterns in incident futures

patterns = self._extract_risk_patterns(incident_futures)

# Look up similar historical incidents

similar_incidents = self.incident_db.find_similar(

state, top_k=3

)

return (

f"{len(incident_futures)} of {len(futures)} simulated futures "

f"predicted incidents. Primary risk factors: {patterns}. "

f"Similar historical incidents: {len(similar_incidents)} in past 18 months."

)The supervisor sees something like:

"Three of five simulated futures predict a dropped load due to wind gusts exceeding threshold. Risk factors: wind speed 23mph (threshold 20mph), crew fatigue (11 hours on site), similar incidents: 2 in past 18 months. Recommended action: postpone crane operation until wind subsides. Override requires supervisor sign-off."

The AI isn't making the decision. It's showing the supervisor what it sees in the possible futures, based on patterns learned from their own incident history. The supervisor can override—maybe they know something the model doesn't—but they override with eyes open.

A natural question: can you actually run five to ten simulated rollouts fast enough for real-time decisions? The answer depends on the domain. For construction safety, decisions like "proceed with crane lift" aren't millisecond-sensitive—a 2-3 second latency for simulation is acceptable. With optimized inference (quantized models, batched rollouts, speculative decoding), the safety team achieved median response times under 800ms for five parallel futures. Healthcare triage has similar tolerances; a nurse spending 30 seconds on a call can absorb a sub-second simulation check. The pattern works less well for truly real-time systems—high-frequency trading, autonomous vehicle control—where the simulation budget is measured in microseconds, not seconds.

The Same Pattern in Healthcare Triage

Hospital call centers face a version of the same problem with even higher stakes. A caller describes symptoms. A triage nurse—or increasingly, an AI assistant—must decide: can this person wait for a clinic appointment tomorrow, do they need urgent care today, or should they call 911 right now?

One health system built a triage simulator following the same pattern. Notice how the state representation shifts from physical environment (site conditions, equipment, crew fatigue) to clinical presentation (symptoms, demographics, red flags)—the structure is identical, but the semantics are domain-specific:

@dataclass

class TriageState:

caller_demographics: dict # age, sex, known conditions

chief_complaint: str

symptom_details: dict

vital_signs: Optional[dict] # if available

conversation_history: List[Message]

red_flags_identified: List[str]

questions_asked: List[str]

@dataclass

class TriageTrajectoryStep:

state: TriageState

triage_action: str # question asked or disposition given

next_state: TriageState

eventual_outcome: Optional[str] # diagnosis, admission, etc.

appropriateness: float # was this the right call?Their trajectories captured the diagnostic dance:

State 0: Caller is a 58-year-old male reporting chest pressure for 20 minutes, mild nausea, no known heart disease.

Action 0: Triage nurse asks about severity, radiation of pain, sweating, and shortness of breath.

State 1: Caller reports pain is 7/10, radiates to left arm, sweating, "something feels wrong."

Action 1: Nurse instructs caller to hang up and call 911 immediately.

State 2: Caller transported to ED, diagnosed with non-STEMI myocardial infarction, admitted. Outcome: appropriate triage, positive.

The hardest cases to model were the edge cases: the 45-year-old woman whose "indigestion" was actually a heart attack, the headache that seemed like a migraine but was a subarachnoid hemorrhage, the child whose mild fever preceded a rapid deterioration into sepsis.

# Edge case: Atypical MI presentation

atypical_mi_trajectory = TriageTrajectoryStep(

state=TriageState(

caller_demographics={"age": 45, "sex": "F", "conditions": ["diabetes"]},

chief_complaint="Indigestion and jaw pain for 2 hours",

symptom_details={

"location": "epigastric, radiating to jaw",

"severity": "moderate",

"associated": ["fatigue", "mild nausea"],

"absent": ["chest pain", "arm pain", "sweating"] # Atypical!

},

red_flags_identified=[], # Easy to miss

questions_asked=[]

),

triage_action="Recommend antacid and call back if symptoms persist",

next_state=TriageState(

# ... 4 hours later

eventual_outcome="STEMI, delayed presentation, cath lab"

),

appropriateness=-1.0 # Under-triage, bad outcome

)By training on borderline presentations alongside clear-cut ones, the simulator learned to reflect the genuine ambiguity that triage teams face. It didn't pretend certainty where none existed.

The health system uses the simulator as a real-time second opinion:

class TriageSecondOpinion:

def __init__(self, simulator, sensitivity_threshold=0.2):

self.simulator = simulator

self.sensitivity_threshold = sensitivity_threshold

def check_disposition(self, state: TriageState,

proposed_disposition: str) -> SecondOpinionResult:

"""Flag potentially under-triaged cases."""

# Simulate outcomes under proposed disposition

futures = self.simulator.simulate_outcomes(

state, proposed_disposition, num_samples=10

)

# Check for adverse outcome patterns

adverse_rate = sum(

1 for f in futures

if f.outcome_severity in ["ED_required", "admission", "ICU", "death"]

) / len(futures)

if (proposed_disposition in ["home_care", "clinic_48h"]

and adverse_rate > self.sensitivity_threshold):

# Find what patterns triggered concern

similar_cases = self.case_db.find_similar_presentations(state)

adverse_similar = [c for c in similar_cases if c.had_adverse_outcome]

return SecondOpinionResult(

flag=True,

risk_level=adverse_rate,

explanation=(

f"Simulator predicts {adverse_rate:.0%} adverse outcome rate. "

f"Pattern similarity to {len(adverse_similar)} prior cases "

f"with unexpected deterioration. Consider: {self._suggest_questions(state)}"

),

suggested_questions=self._suggest_questions(state)

)

return SecondOpinionResult(flag=False, risk_level=adverse_rate)This isn't about replacing clinical judgment. It's about giving clinicians a tool that models possible futures so they can see where the risk spikes before committing to a decision.

What These Examples Share

IT helpdesk. Construction safety. Medical triage. Three very different domains, but the underlying pattern is identical:

- Encode historical interactions as trajectories. States describe the current situation. Actions describe decisions made. Outcomes describe what happened next and whether it was good or bad.

- Train an LLM to predict consequences. Given context and a proposed action, generate what likely happens next and the associated reward. The model learns to simulate the environment, not to give advice.

- Use the simulator for training. Let agents practice on thousands of simulated scenarios, making mistakes and learning from them without real-world consequences.

- Use the simulator as a guardrail. Before high-impact actions, simulate possible futures. If multiple futures look bad, escalate to human judgment rather than proceeding automatically.

The key shift is from asking "what's the right answer?" to asking "what happens if we do this?" Large language models, it turns out, can learn to answer the second question when trained on trajectory data—and that capability opens up a new category of applications.

What We Got Wrong (And What We'd Do Differently)

Honesty compels me to share the mistakes, because anyone attempting this will encounter versions of the same problems.

We underestimated data quality. Our first few models, trained on hastily-extracted trajectories, learned artifacts of our extraction process rather than real patterns. Bad logs became bad trajectories became bad simulators. The three weeks we eventually spent on data cleaning should have been six.

We over-trusted early results. When our first fidelity numbers looked good, we rushed into extended testing without proper consistency validation. We wasted two weeks training agents on a simulator that drifted badly, then discovering our trained agents had learned to exploit the drift. Validate thoroughly before trusting.

We didn't plan for domain shift. Our simulator was trained on tickets from 2022-2023. When we deployed in 2024, we started seeing issues related to new software, new policies, and new error messages that the simulator had never encountered. Simulators need continuous updating:

class ContinuousSimulatorUpdater:

def __init__(self, simulator, update_frequency_days=14):

self.simulator = simulator

self.update_frequency = update_frequency_days

self.trajectory_buffer = []

def ingest_production_trajectory(self, trajectory):

"""Add new real-world trajectory to update buffer."""

self.trajectory_buffer.append(trajectory)

if len(self.trajectory_buffer) >= 500: # Batch threshold

self._trigger_update()

def _trigger_update(self):

"""Fine-tune simulator on recent trajectories."""

# Validate new trajectories

validated = self._validate_trajectories(self.trajectory_buffer)

# Check for distribution shift

drift_score = self._measure_drift(validated)

if drift_score > 0.15:

logging.warning(f"Distribution drift detected: {drift_score}")

# Incremental fine-tuning

self.simulator.fine_tune(

new_trajectories=validated,

epochs=1,

learning_rate=1e-6 # Conservative for incremental updates

)

# Validate updated simulator

new_fidelity = self._measure_fidelity()

if new_fidelity < self.min_fidelity_threshold:

self._rollback()

self.trajectory_buffer = []We underweighted rare events. In the safety and healthcare domains, the events that matter most—serious incidents, missed diagnoses—are by definition rare in the training data. We learned to over-sample them:

def create_balanced_training_set(trajectories, rare_event_boost=5.0):

"""Over-sample trajectories with rare but important outcomes."""

weights = []

for t in trajectories:

outcome = t[-1].outcome

if outcome in ["serious_incident", "death", "missed_diagnosis"]:

weights.append(rare_event_boost)

elif outcome in ["near_miss", "adverse_outcome"]:

weights.append(rare_event_boost * 0.5)

else:

weights.append(1.0)

# Sample with replacement according to weights

indices = np.random.choice(

len(trajectories),

size=len(trajectories),

replace=True,

p=np.array(weights) / sum(weights)

)

return [trajectories[i] for i in indices]We underestimated the sim-to-real gap in human behavior. Our simulator learned patterns from historical data, but real humans do things the simulator never saw: sarcasm that reads as hostility, panic that manifests as terse monosyllables, cultural communication styles that don't match the training distribution. One user responded to our assistant with "Oh great, another bot" and the simulator had never seen that level of preemptive frustration—our agent floundered. In healthcare triage, the gap was starker: a caller in genuine cardiac distress sometimes sounds calm (denial, shock), while an anxious caller with indigestion sounds panicked. The simulator, trained on transcripts, couldn't fully capture the paratext of human crisis. We learned to treat simulation as a lower bound on difficulty—if the agent can't handle simulated users, it definitely can't handle real ones, but success in simulation doesn't guarantee success in production.

And perhaps most importantly: we treated simulation as a replacement for real-world testing rather than a complement to it. Simulation is powerful for finding failure modes and iterating quickly. But it's not a substitute for real deployment. Some problems only emerge when real users with real stakes encounter real systems. The goal is to minimize how many of those problems you discover in production, not to eliminate production testing entirely.

Looking Forward

What excites me most about this approach is how it changes the economics of AI deployment in high-stakes domains.

Today, deploying an AI assistant that makes consequential decisions—about safety, about health, about money—is expensive and risky. Expensive because iteration cycles are slow. Risky because each iteration affects real people. The natural response is caution: deploy conservatively, limit autonomy, keep humans in the loop for everything important.

That caution is appropriate given current tools. But it also means we're leaving value on the table. AI systems that could help—that could catch the risks humans miss, that could handle the volume humans can't sustain—remain constrained because we can't safely let them practice.

Simulation changes the calculation. An organization can explore far more of the design space, test far more edge cases, and arrive at deployment with far more confidence. The AI safety coach can practice on ten thousand simulated scenarios before it ever touches a real construction site. The triage assistant can see every variant of chest pain presentation before it advises its first real caller.

This doesn't eliminate risk. Simulators are imperfect; reality will always contain surprises. But it shifts the discovery of failure modes from production—where failures hurt people—to simulation—where failures are just learning opportunities.

For teams considering this approach, my practical advice is simple: start with data infrastructure. Before you build any models, make sure you can extract clean trajectories from your historical logs. That investment pays dividends in everything downstream.

Then build small, validate carefully, and iterate fast. Your first simulator will be wrong in ways you can't anticipate. The goal isn't perfection on the first try—it's building the feedback loops that let you improve quickly.

And finally, remember that simulation is a tool, not a destination. The goal is better AI systems that serve real people well—safely, reliably, at scale. Simulation helps you get there faster. But the measure of success is always what happens when the AI meets reality.

Technical Foundations

The experiments and implementations described in this article were conducted at the AI Research & Innovation Lab at FutureSignal, where our team focuses on bridging the gap between theoretical AI advances and production-ready enterprise systems. The lab's work on LLM-based world simulation began in early 2024, driven by a practical need: how do you safely deploy AI agents in environments where mistakes have real consequences?

The theoretical foundation for treating LLMs as implicit world models draws from recent research, particularly "From Word to World: Can Large Language Models be Implicit Text-based World Models?". That work established the systematic evaluation methodology—measuring fidelity, consistency, scalability, and agent utility—that informed our experimental design. The benchmark results across text-based environments like ALFWorld, WebShop, and TextWorld provided the rigor we needed to validate our own implementations.

Our primary practical contribution is the Anchoring technique for maintaining simulation coherence over extended rollouts. While the theoretical literature acknowledges drift as a challenge in long-horizon simulation, we developed and validated a concrete algorithmic solution: periodic grounding of simulated states with real observations from a trajectory bank. The _blend_states approach—merging predicted state structure with anchor state realism—emerged from extensive experimentation at the lab. Our results demonstrate that anchoring every four turns improves consistency from 67% to 94% over twenty-turn rollouts, a finding we believe has broad applicability beyond our specific domains.

The cross-domain validation (IT helpdesk, construction safety, healthcare triage) reflects the lab's methodology of stress-testing patterns across multiple verticals before declaring them production-ready. Additional context on safety-critical applications draws from emerging industry practice documented in recent technical reports on agentic AI deployment.

***** All code samples in this article are derived from production implementations, simplified for clarity. The full experimental methodology, including hyperparameter configurations and ablation studies on anchoring intervals, is available through the FutureSignal research portal.